I like seeking the extraordinary in the ordinary: P. Sainath on creating the world's most unique digital archive

Laxmi Panda was one of the youngest recruits of Netaji’s army. Though her state of Orissa recognizes her as a freedom fighter, the Centre refutes the eighty year old Panda’s claim because ‘she did not go to jail.’ Then there is 21 year old Kali Veerapadran, perhaps the only in the world to have mastered Bharatnatyam and three ancient forms of Tamil Folk Dance. Born in the poor fishermen community in Kovalam, he is now determined to resuscitate regional dance forms that are fast dying out. Then there is the potato song, a very serious and heartfelt ode to the vegetable crooned by little tribal girls in a wilderness school. The song is in English.

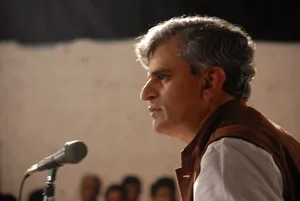

Veteran journalist P. Sainath has been a journalist for some thirty five years, the last twenty two of which he has devoted to writing and reporting about rural India. Indeed he is one of the token few who have. For mainstream media, when they bother with it at all, rural India is a hive of poverty stricken misery. For Sainath, there is no place ‘more fascinating on earth’ than rural India. 833 million people make it their home. They speak 780 languages, practice the most unique and ancient professions in the world and entertain themselves with dance and art forms that have disappeared everywhere else in the country.

To document all these and more Sainath has launched the People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI) - a living journal and a breathing archive showing the everyday lives of everyday people. Sainath writes, “Much of what makes the countryside unique could be gone in 20-30 years. Without any systematic record, visual or oral, to educate us — let alone motivate us — to save this incredible diversity. We are losing worlds and voices within rural India of which future generations will know little or nothing. Even as the present one steadily sheds its own links with those worlds.” It is in our best interests to preserve this precious resource. But if you don’t really connect with rural India or what it represents, then head over on to the site anyway. The searing stories, with their phenomenal breadth and depth, is bound to change your mind. PARI promises to be an enriching experience like no other.

In a heartfelt conversation Sainath extols how important it is for something like PARI to exist, some of the most mind bending professions he’s come across in the course of his work and why rural India is the place where humanity is at its finest.

You said that PARI is the first archive of its kind in India. What makes it unique?

Look at the number of languages we are trying to cover and record? Our aim is to archive every single spoken Indian tongue, which stands at 780 plus. Second, we have the only collection of 8000 black and white images of rural India at work and at leisure. There is no other forum in existence that documents those decades of rural India, starting from the 1980’s when the agrarian crisis began to the present day. Third, it combines different media platforms to give a unique viewing experience. Go on to our site and see the exhibition images on your laptop. You’ll know what I am talking about.

“There are occupations still alive in India that do not exist anywhere else.” In the course of your work what are some of the most eccentric/memorable professions you have come across?

The Khalasis of Malabar who use age old tools and techniques to battle modern day challenges. Another incredible example is the Koilawallah’s of Godda. When I say astonishing, it doesn’t mean that I endorse it or that I like what they do. But the sheer strength and resilience they display takes my breath away.

The koilawallah’s carry 150-250 kg’s of coal on a cycle and walk 42 kilometres to earn a net of 30 rupees. I tried doing it myself one day and managed only 3 kilometres. Every bone in my body ached for weeks afterwards. They do it 3-4 times a week. It is a profession that they have thought of by themselves. It is energy saving they recycle coal relegated to the waste dump. They salvage 3-5 per cent of the coal from the waste. Yet it’s been criminalised and they get punished for it.

You have been a journalist for 35 years. But, with the launch of PARI, are now debuting as an entrepreneur. How was the experience from being a veteran in one field to a newbie in another? What learnings have you acquired during the process of setting up PARI?

I don’t like the term entrepreneur. I am foremost a journalist and any other role I take on is an extension of that.

There are a thousand learning to list. The most significant has been realizing that the digital platform offers a space for doing things which we could never do with a physical platform. TV has no scope for text and still photo. Print has no scope for moving visuals. Digital allows us to do all this and more. We have learnt to create a response design platform which folds back to offer an enhanced and enriched viewing experience.

The other important learning was, and I really knew this in my heart all along but was nice to see it affirmed, how generous and idealistic people can be. Once I announced my intention to launch something like PARI, droves of people have come forward to donate their time, money and expertise into making this vision a reality. Witnessing the beauty of the human spirt up close has helped me strengthen my own convictions enormously.

When asked how your writings will bring about concrete change in rural India you once said, “I try to connect with readers rather than governments, people rather than power. I believe that top level policies of government are more apt to change when democratic pressures build from below.” Do you think storytelling the most effective method of propelling that connection? What different forms of storytelling are you envisioning developing through the site?

I don’t believe there is any single best method for doing anything. That said, storytelling is an excellent method for us. We have highly experienced journalists working and volunteering with us and this is their domain of expertise. We are also learning how much good stuff non- professional journalists can bring to the table.

Storytelling is supremely important. Historically, that is how societies have thrived- by handing down legacies through stories. I think the tragedy of journalism is that it has lost the art of storytelling. Mainstream corporate media has killed it with press releases and PR style news delivery. At PARI we are trying to revive and recapture storytelling in the way that it matters the most.

“Technology cannot be a substitute for social policy. India, and my own home state of Andhra Pradesh, boasts a superpower status in areas like software. Yet the contribution of that field to, say millions of poor dependent on fishing in Andhra Pradesh is virtually nil.” How can the average urban citizen, with all the benefits afforded to them by technology, contribute and help matters along?

A lot of techies are among our volunteers. They want to connect with rural India. They want to be a part of something they feel meaningful about.

When you volunteer with us, you are connecting with your own roots and history. You are connecting with 833 million Indians, whose lives you know very little about. That is a giant part of your society-68 per cent to be precise. I believe that is a fundamental connection we need in our lives.

We have need of good programmers, developers and designers. In the near future we plan to develop a tab which a rural woman of the older generation can use without difficulty. With the expansion of broadband, we think that will happen over the next ten years. A tablet for the rural poor may seem like an outrageous idea, but do remember that lots of who use a cell phone today had no means of doing so five years ago. We feel that techies and user experience professionals are people who can help take this idea forward. The more developers I get volunteering, the happier I am.

That apart, we are appealing to writers, photographers and anyone else to contribute with their set of skills to help us preserve this special slice of our nation.

One of the reasons that help perpetuate urban India’s disinterest with their rural counterpart is the mainstream media’s affinity to zero in on the tragedy and present a one dimensional account of the lives people there lead. Yet PARI shows rural India to be a rich and variant microcosm, one that is utterly unique and marches to its own rhythm. What have we been missing?

I agree with you in that what they have done is bad. But I don't think they have done much at all to begin with. The little coverage they have afforded to farmer suicides and like has happened because of people like me and my close colleagues.

In fact when the mainstream media does deign to cover stories of development in the countryside, I fear they do more harm than good. They mindlessly celebrate the purchasing power of successful farmers. This guy was just a small farmer and now he's bought a car. They don't go back and see when he's had to sell his car and his flat because of debt. The real success stories are of no interest to them at all. One guy becomes a crorepati and they make that an issue.

The most awe inspiring thing to me is the resilience of the ordinary poor Indian. Their sheer resilience in the face of adversity and their tolerance about near impossible circumstances- to me that is magic. They are able to do things that you or I could never dream of. The average Indian woman in rural India spends one third of her waking life on chores like fetching water from miles away, fetching firewood from a huge distance and gathering fodder. She keeps the family going. She keeps society going. The unflinching determination of these people to provide for their families and to seek work with dignity is breath taking. It is human spirit at its mightiest. I am constantly seeking the extraordinary in the ordinary and it is here that I find it in its truest form.